Professor Booyong Lee, whose research focuses on functional foods and nutrigenomics, took the stage with a notably approachable presence at this year’s symposium. Although the topic centered on advanced genetic concepts, she captivated the audience with an intriguing premise: “Food and nutrition can influence not only our own health, but also the future of our descendants.” In an era overflowing with new dietary trends, she opened her talk by examining everyday eating habits and observable health patterns around us—through the analytical lens of a scientist.

DNA, Genes, and Decoding the Blueprint of Life

Professor Lee began by outlining the fundamentals of DNA and gene research. Since Watson and Crick revealed the double-helix structure of human DNA in 1953—establishing that our entire genetic blueprint resides within this structure—genetic decoding technologies have advanced at remarkable speed. As research progressed, public interest in what constitutes a “healthy gene” also increased.

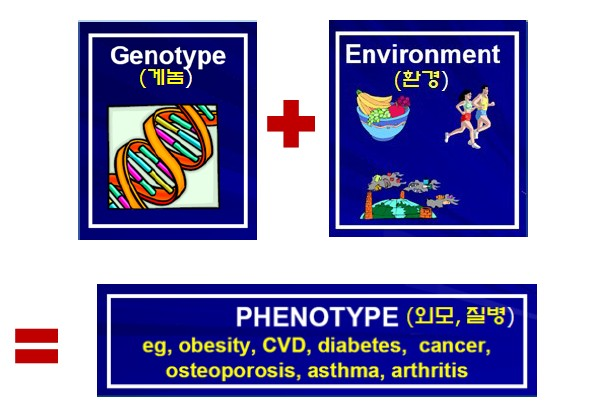

Addressing the question “How can we pass on healthier genes?”, she explained that the answer lies in understanding the difference between genotype and phenotype. The genotype is the immutable genetic blueprint inherited equally from each parent, whereas the phenotype represents the traits shaped by environment and diet. In other words, our current health and physical characteristics are the cumulative result of what we have eaten and how we have lived. Crucially, these phenotypic changes can be transmitted to future generations through epigenetic mechanisms.

Why Diet Matters

Citing Wolffe’s 1999 concept of epigenetics, she emphasized that dietary habits play a critical role in regulating gene expression. Epigenetics shows that even without altering the DNA sequence itself, the way genes are expressed can shift—changing one’s health or disease risk. These changes can be passed across generations, yet can also be reversed when environmental conditions improve. In other words, negative epigenetic influences are not irreversible.

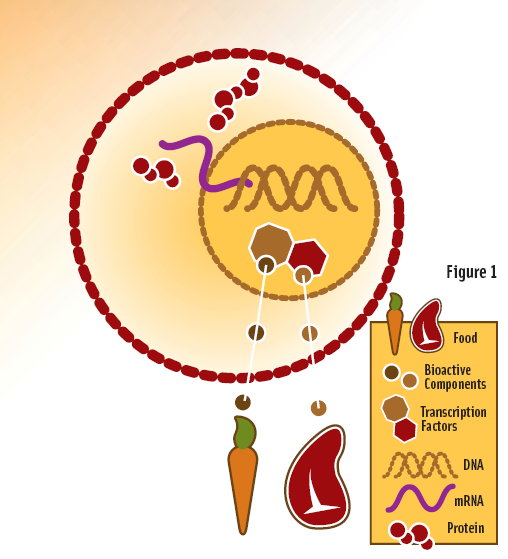

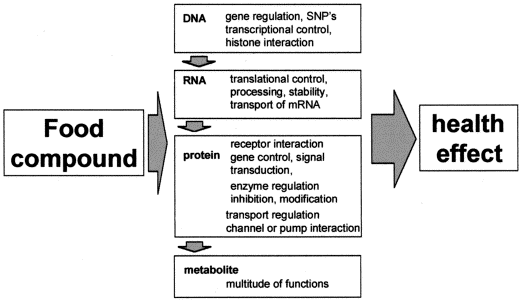

What does it mean for “DNA to be expressed”? She illustrated this with concrete examples: when methyl groups attach to DNA or when histone proteins undergo modification, the level of gene expression can change. This means that the nutrients or chemicals we consume can directly influence transcriptional regulation inside our cells.

- Methyl group: the basic unit of an organic compound, consisting of one carbon and three hydrogen atoms (–CH₃)

Histone: protein around which DNA is wrapped;

Acetyl group: a small chemical group (–COCH₃) that can modify histones

Among all environmental factors, food is most closely tied to epigenetic change because it is consumed daily and influences the body continuously. Proper nutrition can reduce disease risk, and well-regulated gene expression can, in turn, be passed on beneficially to the next generation.

Beta-Carotene, Vitamin A, and the Interaction of Nutrients

Professor Lee visualized this process using an engaging example. When iron-rich meat is consumed together with foods high in beta-carotene or vitamin A—such as carrots—the absorbed nutrients enter the cell and influence transcription recognition, thereby regulating the pathways that lead to protein production. In essence, what we eat and how we combine foods can reshape gene expression at the cellular level.

She continued by presenting real-world evidence linking dietary patterns to disease. A study published 15 years ago showed that Koreans living long-term in the United States consumed a substantially higher-fat Western diet compared to Koreans living in Korea. As a result, they exhibited increased rates of obesity and cardiovascular diseases. This finding underscores how strongly environment and diet can override genetic predispositions and shape actual health outcomes.

The Dutch Famine Cohort Study

Another powerful example she highlighted was the Dutch Famine Cohort Study, which tracked roughly 2,000 individuals born during the severe famine caused by German blockades in the Netherlands during World War II. Decades of follow-up revealed that children exposed to maternal malnutrition in utero underwent epigenetic adaptations that shifted their metabolic profile into a “thrifty” mode—efficiently storing calories even when later raised in abundance. Consequently, these individuals showed higher rates of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, a pattern that continued into the next generation.

Professor Lee emphasized that this study represents “one of the clearest demonstrations of how powerfully epigenetics can shape health across generations.”

He concluded by noting that the human body contains approximately three billion base pairs and around 30,000 genes, and that our traits are determined not merely by which genes we carry, but by which genes are activated and which are suppressed—a process deeply influenced by lifestyle choices. Our present dietary habits and daily behaviors can imprint themselves onto our genes and be transmitted to our descendants.

In closing, He referenced David Moore’s The Developing Genome, summarizing its key message: “Genes are not destiny; they are stories that can be rewritten through experience and choice.”

He ended his talk with a resonant reminder: the choices we make at the dining table today help shape the healthy phenotypes of future generations.